I think about the symmetry or lack of symmetry in the found object (a man made object, the building and land) aspect of” Symbiosis” and I think about ways to balance it. In contrast every time I look at an element of the installation (a nature made element) I see nature has a design formula. I have noticed the Symmetry in nature is redundant and it seems the tech world is looking too.

Endangered Knowledge: The Soul of Humus — The Bison in the Texaco Star

The Bison in the Texaco Star

The third pasture/exhibition

As in agriculture that rejuvenates the soil, the bison has rotated to its third pasture/exhibition. It began in a historic grain silo/art venue in Sculpture Month Houston's Altamira, which considered modern caveman's materials and message to the future, followed by the Blue Norther exhibit, where the bison addressed extreme weather's connection to soil. Now it brings its message to the Houston Forever exhibition in the former Texaco Building in downtown Houston.

The Star building, former home of Texaco, the company that developed the Spindletop gusher in 1901 and took the US into the oil age, is a key location in the sculpture's rotation. The bison in the Star embodies our civilization's conflict "between" ecology and commerce. Before Spindletop, oil was primarily used for lighting and as a lubricant. With Spindletop's abundance, Texaco began marketing petroleum for mass consumption. What can we learn about natural carbon cycling through the soil from the herd's eating and waste habits — also called consumption and regeneration — contrasted with the development of the energy industry and our society's mass consumption without individual responsibility for regeneration? Comparing and contrasting these two energy sources, both receive energy from the earth: one where each consumer returns carbon to the soil and the other supplying a chain of energy but still trying to figure out how to repay its debt of carbon for future generations. Integrating natural systems of regeneration can steer our innovation and creative minds to a future in which consumption, conservation and regeneration of earth's resources are in balance.

Rosinweed sunflower bloom and spider.

Tiny spent sunflower bloom/seed head-the colors - suttle and faded, still rich and deep. The shapes of the seeds as they dried ❤️ The beauty of the natural world when you stop and look. I studied this dried object probably 4 minutes turning it in my fingers watching the white blooms from the crepe myrtle attached by the thread of a spider and then turning it over hiding underneath- a creature. As we enter the Anthropocene, saving insects is a priority in “Symbiosis.” When I edit out any materials such as this elegant, delicate, dried Rosinweed sunflower head from the garden, I do not bag them and put them in a trash can. I chop and drop. This tiny spider is evidence that chopping and dropping not only builds soil and saves money it also saves insects.

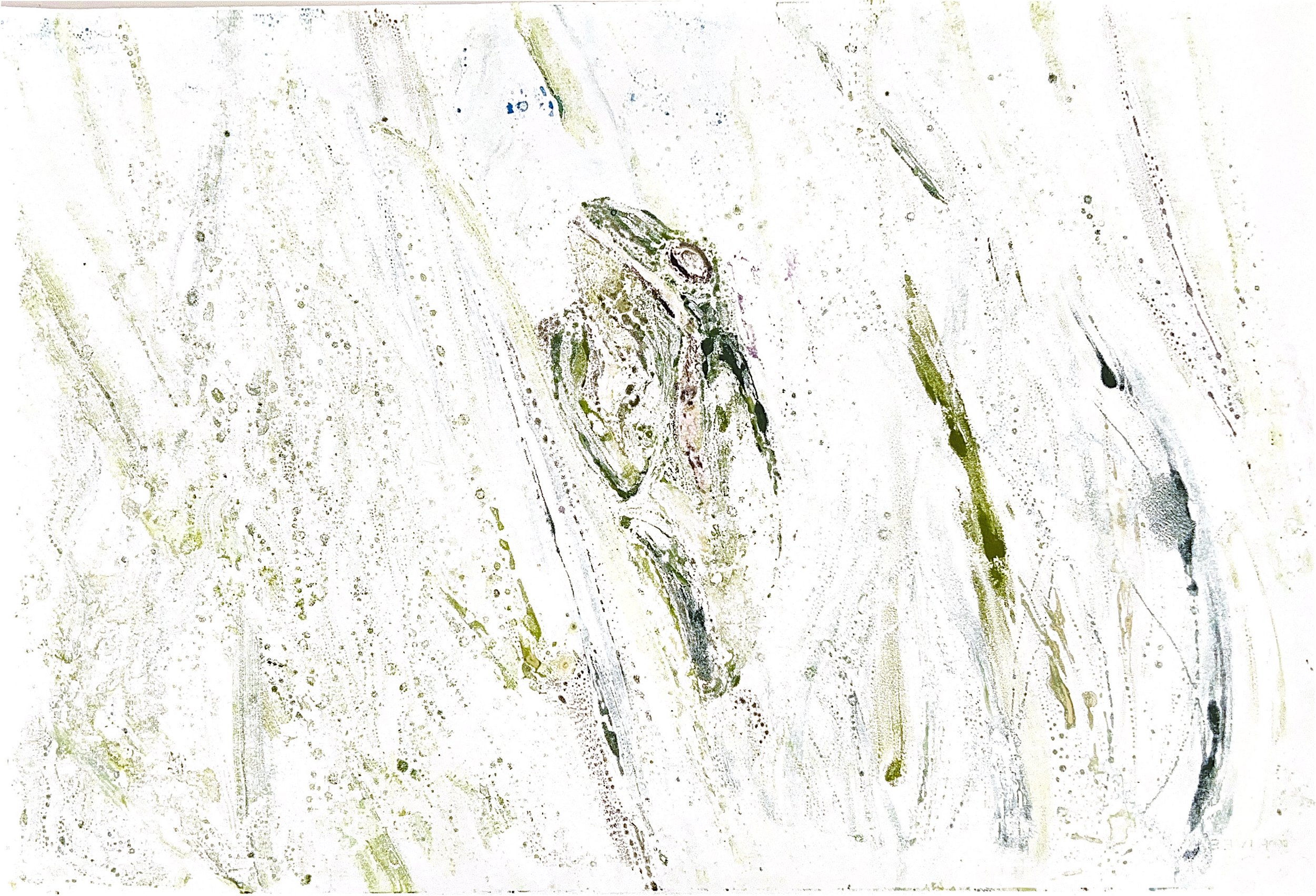

Green Tree Frog Eggs

We had the first big spring rain the week before Mother’s Day. That Saturday , I stopped in "Symbiosis" to check out the wildlife and chat with anyone visiting the exhibitions. To my surprise, the pond is now a green tree frog nursery. The trough pond is surrounded by tall native plants that tree frogs love. I have not seen the green tree frogs since last year, I thought I heard them one night few weeks ago. Mother toads and tree frogs have to have water to lay their eggs. I believe tree frogs lay their eggs on limbs where they fall in the water.

Above are a few watercolor monotypes I did of the tree frog.

Symbiosis- Food chain - Mockingbirds and Toads

On an early July morning, with a new camera in my hands, I was hopeful the zoom lens would document unseen details in Symbiosis. I focused the lens on the “feed me” gesture of the juvenile bird. Later zooming in on the image on my computer revealed the middle of the food chain — A Mockingbird feeding a juvenile, not a caterpillar, wasp, or an insect but a slight blurry silhouette of a toad. On my laptop, I witnessed the middle of the food chain, a moment in a living sculpture, evidence of a healthy ecosystem and hope in a sea of asphalt on the Gulf Coast.

In Symbiosis building, a food chain that has not been exposed to chemicals or pesticides is crucial to building a base and armature that supports the more visible kinetic elements — wildlife and humans, the upper food chain. Its strength is critical to the success of the whole.

I use systems thinking to plan and organize my sculptural additions and extractions to the piece. In this case, not using pesticides to control insect pests or unruly vegetation is a priority. The water feature in the garden invites mosquitos, dragonflies, frogs, toads, and aquatic insects to lay their eggs in the still water. The tadpoles, nymphs, and Texas mosquito fish eat the mosquito larvae.

In the work, all of the individual species are linked by the health and abundance of the lower species. “Symbiosis” is an element of the “living” Earth, a community of organisms existing within the Art center's sculpture garden and social sculpture.

Salvia arurea and It’s Allies

The earth tone Horace's dusky wing skipper alights on the side of a blue dragon head shaped blossom. The blooms are stacked in a whorl pattern on it’s square green stem forming a Salvia azurea spike . The upper lip of the tubular blossom is hooded and is shorter than the three-lobed lower lip, which serves as a landing pad for pollinators. The Dusky wings long curled proboscis unfolds into the white throat of the delicate bloom to which it clings. In return for nectar the Dusky wing pollinates the flower.

The native Salvia produces square tall arching stems that terminate into large, branching, flower spikes. It’s opposite placed grey-green leaves are narrow with slight notches. If you rub the leaves you release a minty aroma.

I see in most gardens the hybrid Salvia with compact green foliage. It is unfortunate that the pollinators are not attracted to the short hybrid.

Salvia is a favorite of North American butterflies, bees, moths and hummingbirds.

Loving Dead Things

I specifically leave dried dead plant materials in the garden for 3 beautiful reasons. First many butterflies leave their eggs on the under side of dead leaves and many chrysalis look like crumpled leaves. If I bag and dispose off all the dead plant material we loose endangered insects. 2nd, birds need the seeds for nutrition. 3rd I love the soft earth tones they offer. One of the principles I apply to the garden is protecting the soil with plants.

As a result symbiosis is a sea of green. Traditionally contemporary gardens leave the bare ground around each plant. This results in compacted soil . A garden that adheres to regenerative agriculture principles needs earth tones to break up the green.

That Was Then This is Now.

July 2020 - the sculpture garden as it was when Stephanie and I first discussed the project.

February 2021. After the Texas freeze

May 2022 - 12 months from installation.

I ❤️Aphids and what insects tell us.

I Leave aphids be. It may look alarming but It is a necessary step in regaining a balance of good bugs and bad in "Symbiosis". I am looking forward to see which beneficial insects show up to help the planet manage the aphids. Aphids feed through a needle-like mouthpart. After they insert their mouthpart into a plant's tissue, they then use it like a straw to suck out plant juices. The do not kill the host plant. Aphids aid benefical bugs they are food for thousands of different species of predatory insects. As protein Aphids help build a broad diversity of beneficial bugs in nature.

After writing this post I came across one of the most interesting insect control articles.

We have so much to unlearn.

Land Art vs Living Sculpture

Land art or earth art has paved the way for what I hope will become a new art movement.

The Tate defines Land art or earth art as the art made directly in the landscape, sculpting the land itself into earthworks or making structures in the landscape using natural materials such as rocks or twigs. With the Tate's definitions, Symbiosis is land art, a part of the conceptual art movement, and environmental art.

What separates Symbiosis from these traditional classifications of art are the concepts I apply to my creative decision-making process and the materials I use support and regenerate life. It values all living creatures as participants in the creative process.

My process for creating a living sculpture involves holistic decision-making. First, I incorporate a systems thinking approach to create a functional balance between the healthy ecosystem, human economics and societal landscape norms. For example, contemporary landscape designs are structured in monocrop rows or groupings separated with bare earth. To maintain the manicured design, weed-killing chemicals and gas-operated mowers and edgers are the most economical. This lack of plant diversity, geometric-in-shape groomed plantings, and chemical inputs make these landscapes uninhabitable for a diversity of wildlife other than a few lizards. For many valuable insects and microorganisms, the inputs are deadly. These designs do not consider supporting the food chain necessary in a healthy ecosystem. In Symbiosis, I keep the ground covered with a diversity of plantings that drift in and out of each other and with the seasons; this provides camouflage from predators, nesting materials, and a variety of nourishment all year. Weeds fit into this landscape and help build the microorganisms and structure or armature in the soil. This less structured planting design is balanced with a classical symmetrical layout. Symbiosis is designed to build the food chain. The maintenance required is easily accomplished with handheld clippers. The clippings are put back into the garden to decompose by insects and natural systems that build the soil health and retain water and carbon, or into a vase to be enjoyed. Ultimately Lawndale benefits economically through lower maintenance, chemical inputs, and utility costs, while enjoying a toxin-free environment—living sculpture.

I use materials that support plants and wildlife specific to the site's ecological history. I begin with a water source, animal waste and decaying plant materials native to the area. These materials build habitat and nourishment for microorganisms in the soil, in the water feature and up the food chain to sustain each other in extreme Texas weather. When combined with our clay soil they: store carbon, cool and return water to the aquifer, support life beneficial to humans and keep harmful pests at bay. In addition, they assist in cleaning the air, slowing rainwater, and reducing land erosion.

For example, I have created symbiotic relationships between humans, mosquitos, dragonflies, fish, and chemical-free water. In a hot environment, animals need a freshwater source to drink and reproduce. I installed a small pond without a filter or pump. Using plants to filter the water, I utilize the eating and waste habits of the Texas Mosquitofish to control the algae and build the water's biology. Mosquitos and dragonflies are attracted to still water with a balance of healthy bacteria and algae to deposit their larvae. The larvae become protein for the fish. Attracted by the water source, the dragonflies hover above the garden and on dried plant materials hunting mosquitos, supporting human health. Lawndale benefits economically by not utilizing an electric pump, needing a mosquito misting machine or pesticides and enjoys the beauty of the water feature and a kinetic, ephemeral rainbow of dragonflies hovering and darting over the living sculpture.

In Symbiosis, as the lower food chains develop, it begins to regenerate life and recover what is lost. Perpetual, it is art for now and future generations. In a living sculpture, the ways to evaluate it are space, shape, line, color, texture and regeneration.

I submit below images and descriptions of symbiotic relationships, ephemeral parts of the installation from April 2021-April 2022.

Dung loving birds nest fungus

Gulf Fritillary butterfly on rosin weed sunflower. It roots can extend 16’.

image by Nash Baker courtesy of Lawndale Art Center

Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) on Monarda citriodora lemon beebalm image by Nash Baker courtesy of Lawndale Art Center.

Gulf fritillary butterfly on Gulf verain Verbena xutha image by Nash Baker courtesy of Lawndale Art Center

Battus philenor a pipevine swallowtail

Gulf fritillary on Rudkeckia hirta

Long-tailed skipper Urbanus proteus on Salvia azure

Junonia coenia the common buckeye butterfly on a blanket flower Gaillardia puchella with dew drops.

Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) on scarlet sage Salvia coccinea.

Gulf Fritillary butterfly on purple cone flower

Red arrow Rhodothemis lieftincki on dead olive tree limb.

Mosquito control and water source for winged species.

Past bushy blue stem and Seaside Golden rod. I leave them through March so the winds can spread their seeds to other gardens, and to provide shelter for birds, tree frogs, toads, and field mice.

Plathemis Whitetail Skimmer

Mosquito control and water source for winged species.

Past bushy blue stem and Seaside Golden rod. I leave them through March so the winds can spread their seeds to other gardens, and to provide shelter for birds, tree frogs, toads, and field mice.

Brown skipper and Rudbeckia hirta

water + air + citizens - the actual event

14” X 6” X 6”

Found objects — a glass jar and cork lid, shale, charcoal, mesh, distilled water, Springtails, a Monarch carcass, living soil, Horseherb (Calyptocarpus vialis), Bigfoot Waterclover Marsilea macropoda, two chrysalides, two oyster shells, decaying bee balm bloom and a bird skeleton.

water + air + citizen

I documented the event by having the participants take a small step as a community to build a healthy functioning ecosystem collectively. Earth's water system is a closed water system. Although we can make soil, we cannot make more water.

Before the discussions began as a symbolic gesture, each person added an element to provide the future with a water system to sustain life on Earth. The objects in the documentation are found objects — a glass jar and cork lid, shale, charcoal, mesh, distilled water, springtails to eat the fungus, and a Monarch carcass to envision the future. Sourced from Symbiosis, the piece includes living soil, Horseherb (Calyptocarpus vialis), Bigfoot Waterclover Marsilea macropoda, two chrysalides, two oyster shells, decaying plant matter and a bird skeleton.

After the event, I added elements present in urban earthly healthy ecosystems; the bird skeleton I found in Symbiosis last spring, two chrysalides vacated by butterflies and left on Lawndale's fence, a dried lemon bee balm bloom, and lastly, a past Monarch butterfly. Monarchs were not witnessed in Symbiosis' first year. I found this Monarch on the sidewalk of my neighborhood. To recover endangered species, we must envision them in our terrain, provide habitat and plants that give them nectar. I placed the terrarium on two broken concrete pavers. As an urban community, we took the first step we successfully built an ecosystem where our actions support natural systems that temper weather and provide clean water and air.

In 2021 I proposed to Lawndale a social Sculpture that addresses the three ways humans intersect soil in Houston. The way we treat our soil impacts two ingredients necessary to sustain life on Earth, water and air.

Public policy, Design industry, and Art activism.

Water + Air + Citizens is a discussion that looks at three ways Houstonians (humanity) impact these natural systems through urban landscapes.

Medians, yards, gardens, lots, parks, blocks are all surfaces of Earth. But, by any name, the skin of our planet purifies its water and regulates its atmosphere.

As the event grew close, I began to see a bigger picture, another layer to the work. In my sculpture practice, this is a common occurrence. In this case, I became aware that the title I chose for the sculpture is three of the most potent elements in weather. First, with water, we have floods and hurricanes. We are hit with hurricanes, tornadoes, and dust bowls in the air. Finally, citizens' power of public opinion is a tremendous force and often overcomes the common sense of individuals and leaders.

Symbiosis - Pollack

When I study the areas of the work that visibly support the most wildlife in Symbiosis I often think of the the most notable works of Pollock. I am presently reading The Extended Mind by A.M. Paul. In the chapter on thinking in natural spaces she wrote. - “Nature changed Pollocks thinking - gently tempering his raging in-tensity- and it also changed his art. In New York, Pollock worked at an easel, painting intricate, involved designs. In Springs, where he worked in a converted barn full of light and views of nature, he began spreading his canvases on the floor and pouring or flinging paint from above. Art critics view this period of Pollocks life as the high point of his career, the years when he produced "drip painting" masterpieces like Shimmering Substance (1946) and Autumn Rhythm” the extended Mind by A.M. Paul. I often see Pollockness in “Symbiosis”. This images especially reminds me of his Autumn Rhythm. In “symbiosis” it is winter shelter. This scarlet sage was damaged after the freeze.

Symbiosis - dead plants

The February freeze left its mark in the garden. Above ground, the Scarlet salvia, Salvia coccinea, was left in the form of crispy brown twigs and leaves. Below ground, the roots were protected by the moisture and living organisms in the soil. The beauty of a perennial is the roots are weather tough and will sprout new life this spring.

In our present culture, these dead limbs would be removed from the site immediately. They remove these dead plants when the weather is still harsh, leaving the ground bare the life that lives in and on it vulnerable. In Symbiosis, these bronze arched stems, and their bi-petaled crumpled leaves are sheltered from downpours, wind, and predators. I leave them. Their leaves and stems may not be a beautiful green, drawing energy from sunlight and water from the earth producing sugar to boost growth and oxygen released into the air. They absorb heat, warm, and protect the ground and living organisms. When March winds come, their seeds fly to new gardens and bare spots ground. When our weather warms, I will chop these dried elements to return to dust. They will become sustenance for bacteria, nematodes, fungi, and earthworms. In life and death, the plants are valuable in landscapes.

Endangered Knowledge: The Soul of Humus — the next paddock and long term plan.

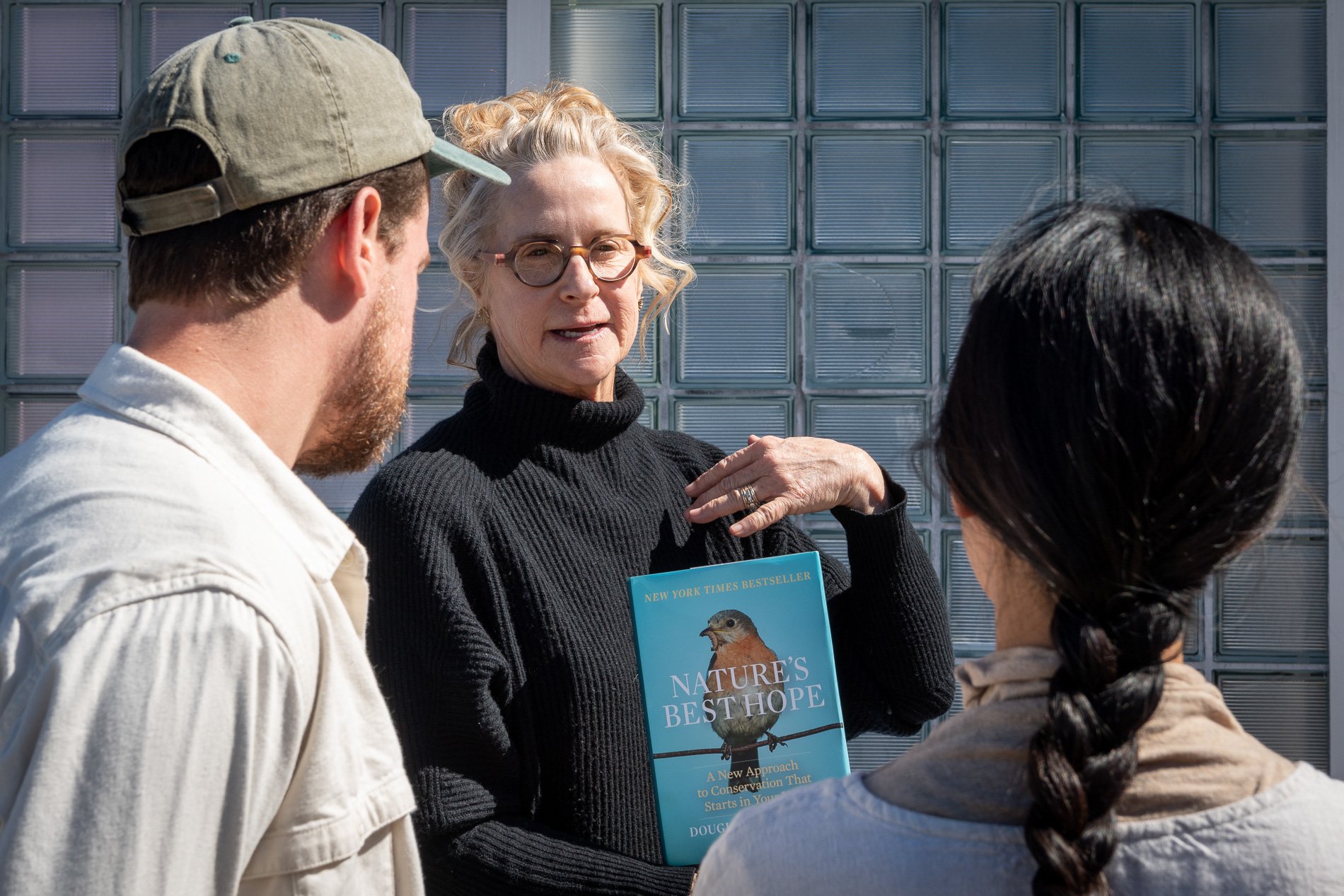

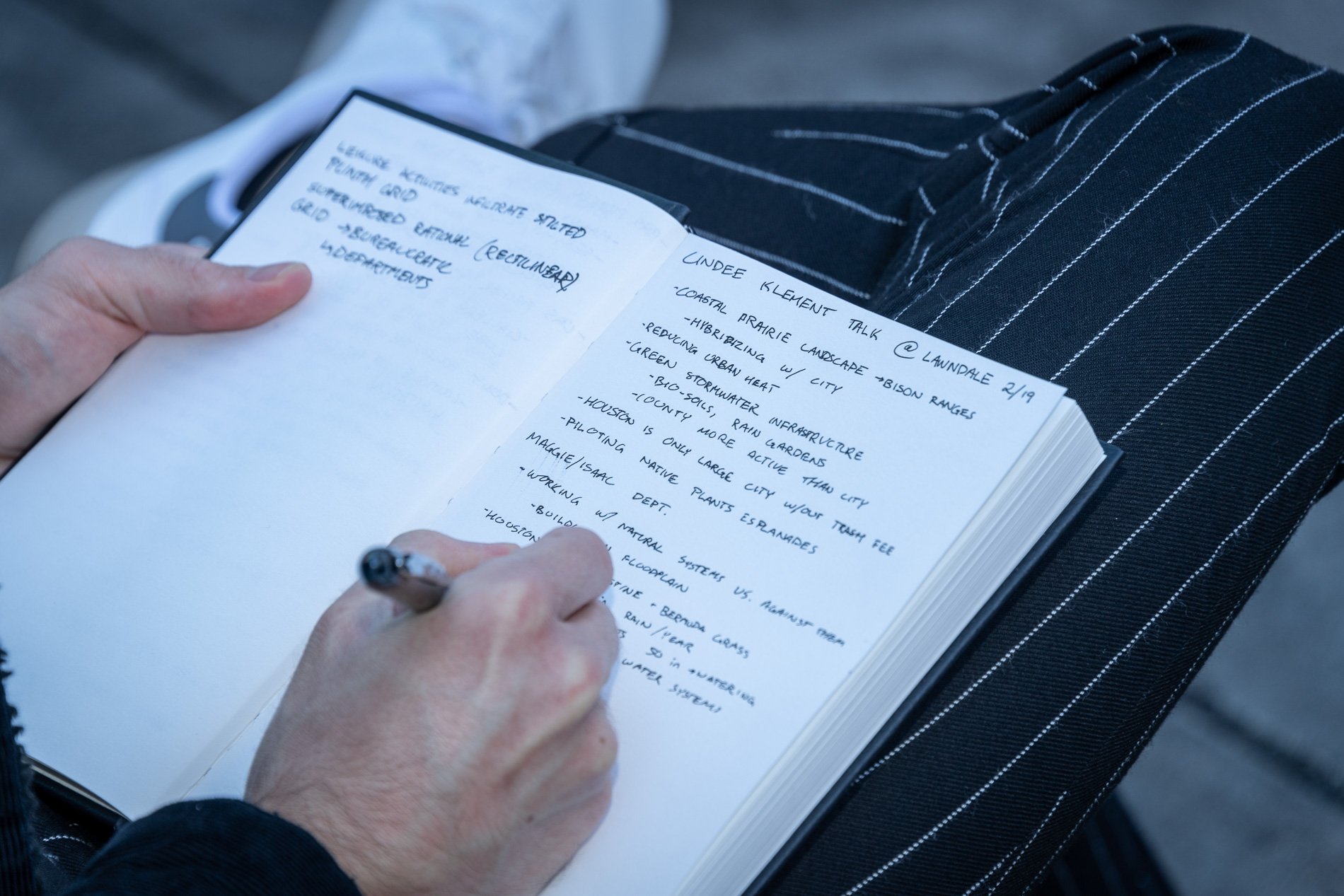

Cindee Travis Klement

Endangered Knowledge: The Soul of Humus

Long Term Proposal - sponsorship and site selection

Sponsorship from the energy industry can mutually benefit from my long-term plan.

How can this work be valuable to the energy industry?

I read in the Houston Chronicle that oil firms wrestle with public image. And, I have read that these same companies are starting to look at agriculture to regenerate the planet and return carbon to our soil for future generations. So, sponsoring my carbons sequestering figurative sculpture can be a tool to build a positive public image, support the environment through educating the public with the natural history it represents, and support the arts and female artists.

What is my long-term vision for the piece?

I believe that we cannot fix our environmental issues if we as a society do not understand how our environment works. Therefore, I made Endangered Knowledge: The Soul of Humus an educational, ecological work for now and for civilizations to come. My vision is to exhibit the work in a high-traffic location on Houston's Buffalo Bayou with the Energy city skyline behind it. The tension of the great bison created out of the indigenous earth and organic material placed against the glass skyline of the energy city will permanently record this endangered knowledge to the citizens and visitors of the coastal prairies collective memory. It will plant the seeds to holistically balance the needs of humanity and wildlife in urban landscapes. I will be a reminder of our collective responsibility of sequestering carbon, soaking up rainwater, and cooling the planet, extending our time on the earth. For the piece to stand the weather, it will be cast in bronze.

How can this sculpture be valuable to the Buffalo Bayou Partnership and the city of Houston?

In the early 2000s, I chaired my daughter's high school environmental social service project. I organized a clean-up on Buffalo bayou for the 16-year-olds. We were pretty new to Houston, and I was curious about Buffalo Bayou's name. After some research, I learned the last bison herd was seen just after the Alamo. A few years later, I discovered the connection between grazing herds, soil health, food production, sequestering carbon, and soaking up rainwater. All these things are crucial to human existence, yet it is unknown by most of the population. Buffalo Bayou is Houston's most significant natural resource, a natural landmark. It is the site my environmental sculpture can have the most important environmental impact. Below is an image of the site I envision for the piece.

What will it cost?

Over the last eight years, I have built a relationship with Legacy Fine Arts Foundry, a minority woman-owned foundry. We have worked out a process to direct cast organic material into bronze. I can show you samples in my studio. The work will not look like a bronze monument it will be a work of art. The process is similar to that of Joe Havel and Linda Ridgeway but adapted to my organic materials. This piece will take the process of direct casting to a whole new level. I project the project will come in between $150,000 - $260,000. That would include a production cost of roughly $100,000., transportation, engineering fees, site preparation, lighting, installation, insurance, artist, consultant fees, etc. Much of the cost is dependent on the site.

The image above is the type of skyline I envision in the background of the proposed installation. The old male bison would be grazing on low-growing native prairie grasses. A few feet behind him, visitors would see cast bronze dung, mushrooms, birds, and dung beetles. The work would not need the granite pedestal as pictured. There are also some suitable sites on Memorial.

Water + Air + Citizens- social sculpture

Water + Air + Citizens

February 19th, 2022, at 2:00 pm

—social sculpture—

Reshaping soil in Houston: Public policy, Design industry, and Art

Lawndale Art Center's Mary E. Bawden Sculpture Garden

Dear friends and family,

Lawndale and I invite you to a public conversation with Sallie Alcorn (Houston City Councilmember), Maggie Tsang (2021-2023 Wortham Fellow at Rice School of Architecture, Managing Principal, Co-Founder of Dept.), Isaac Stein (Design Principal and Co-Founder of Dept.), and myself (exhibiting artist).

I have organized a social sculpture event, a conversation that will explore Houston's landscape practices and ecologies. Together, the speakers and I will consider the diverse ways that Houstonians can positively impact the local environment, looking closely at the design and development of medians, yards, gardens, lots, parks, and blocks.

Image - Symbiosis, Spotted Horsemint, a volunteer Texas native plant, and a Texas native wild bee. The bee is a Two-spotted Longhorn Bee, Melissodes bimaculatus one of the threatened 400 native bee species of Texas.

Altamira- video Endangered Knowledge: Soul of humus -

courtesy of Sculoture month.

Endangered Knowledge:The Soul of Humus - Bluenest beef

A few years ago I went o a soil conference in Solado, Texas. Through that conference I was referred to Russ Conser.

In November I had a meeting with Russ Conser of Bluenest beef to show him and his wife the bison Sculpture. The next week he wrote the below post on his blog.

“Two weeks ago, I sent you an email about migrating bison and birds and how they might help us rediscover how the health of people and planet and planet were intrinsically connected. It was a story of how the soils of both my birthplace and my current home were created by a symbiotic relationship between lush and diverse prairies and the bison that roamed them. My friend Dan wrote a book that went on for many thousands of words, and I could have gone on for pages elaborating myself, but in response to that email, I got one of those ‘pictures that says a thousand words.’

You see, one of our customers, Cindee Klement, sent me photos of her new sculpture project that told this same story profoundly with no words at all. See her here, with her latest project “Endangered Knowledge: The Soul of Humus”:

Last Thursday, I went for a visit to see it myself in a trip that left me speechless. I learned that Cindee grew up on an arid but irrigated farm in far west Texas. She had heard unbelievable stories of the grasses that were there long before her birth in a land that is now desert. Today, she is a fellow Houstonian who lives along the banks of our primary waterway, Buffalo Bayou, and realized that that was a name of deep significance to our lost heritage whose meaning had been forgotten.

Having been inspired the story of grazing animals that collaborated with prairie grasses to originally create our region’s life-giving carbon-storing soils, she decided to create an epic work of art that flips that script – creating a bison out of soil and the grasses that made them.

Underneath is a structure of welded and woven steel, but the dirt, and grass and roots are all you see. The majestic beast’s hide is made of clay, its coat of diverse grasses, and the hair on its face of fine fibrous roots. The birds on its back, which were inspired by a visit Cindee made to a regenerative bison ranch, are made of bronze, as is the manure left along the trail to its present ‘grazing’ site. This creates a somewhat surreal visual dynamic between the daunting mass of the clay and grass beast and the import of the life cycling all around it.

Here it is in full as best as I could capture it in a single image:

The body is large and powerful - the eyes almost haunting. You can almost feel him contemplating the meaning of his next bite in gratitude to the soil and grass emerging from it. I am struck by how no words, no factoid, nor no chart my scientific mind could ever produce might compete with this work of art. Cindee’s story makes it compelling, but the art truly speaks for itself. It’s powerful. It’s epic.

The sculpture is currently on display in an old concrete grain silo along the train tracks that parallel the bayou named after its ancestors. Just a mile or so downstream, lies the point on the bayou where nearly 200 years ago the Allen Brother’s founded what became the city of Houston. But for at least another 11,000 years before that, the indigenous people who lived here hunted bison along that same bayou using the waterway itself as part of the hunt. Cindee’s sculpture strikes as something that is at once a fitting metaphor for our region’s history - a former wetland prairie now a hub of industry and technology covered by sprawling concrete, and also a forward looking ecological ‘golem’ – a creature created literally of the place to (hopefully) serve the purpose of the place.

Cindee wants her sculpture to be a message to the future – a message of reimagining how we humans might live respectfully and productively within and as a part of this coastal prairie ecosystem. But its literal future is still uncertain. Cindee is considering options to transform the original sculpture into bronze for permanent outdoor exhibition. Personally, I would like to see it on display as part of this project where many people might see and hear the message on a day in the park, thus putting this sculpture worth more than a thousand words in a place where the people can rediscover and remember forever this “Endangered Knowledge.”

You can learn more about the sculpture and Cindee’s other work on her web site. For those in (or soon passing through) this region, the sculpture will be on display through December 4, 2021 at the “Sawyer Yards” Art Studio as part of an exhibit appropriately titled “Altamira: The Primal Urge to Create.”

Russ Conser

Blue Nest Beef Co-Founder & CEO

Weed Out

As geologists and environmentalists battle, “are we in the Holocene epoch or have we made our mark on Earth and entered a new geological period, the Anthropocene?”, I ponder weeds.

The term weed, in the Holocene, is a plant that sticks out in a monoculture. From a bipedal primate’s perspective, a weed isn’t like all the surrounding plants: we undervalue it—because it “looks” different. From a human who spells her name Cindee with two ee’s, I have to say I am attracted to weeds and not just because of the ees. Since my first installation in Symbiosis, on February 14, 2021, I have thought a lot about the word, verb, and the thing weed, asking myself so many questions and finding answers in this urban garden.

In nature and in Symbiosis, I observe weeds and now see them as Earth’s first responders to large or small ecological disasters. Weeds are seeds, roots, stems, leaves, berries, and blooms—organic matter. Weeds are vegetative volunteers in the ecological services division of Earth; they provide emergency services for its living organisms above and below ground. Hear me out — when the Earth’s green skin is left bare, tilled, stripped, eroded, poisoned, burned, flooded, neglected, or disturbed by natural or human occurrences, Mother Earth cherry-picks from embryos sleeping in the soil her first responders—our weeds-seeds. Like our own“compounded prescriptions,” seeds are biologically programmed for the site’s specific ecological condition—temperature, moisture, and daylight—to grow fast and spread quickly; they are speed healers. As they mature, I see emergency room physicians administering oxygen masks for underground organisms, protective bandages for the Earth’s epidermis, and poison antidotes. Their organic matter lowers the Earth’stemperatures, thereby keeping soil and its living microorganisms alive. And they provide shelter, food, and nectar for the site’s microorganisms, wildlife, and humans. These ecological first responders are full-service providers, slowing rainwater, reducing soil erosion, replenishing the aquifer, cooling the planet, sequestering carbon, and stabilizing it in the ground for those debating geological periods to come.

From a sculptural perspective, if the shape, texture, or color of a volunteer first responder “weed” does not satisfy my artistic vision, I no longer yank it out of the ground in a knee-jerk response. I stop—look—think, why was it sent in? I take a holistic approach. I weigh the service it is providing our above and below ground micro-ecosystem, the armature that supports the life of the sculpture. I then consider what human adjustments I might implement to holistically balance these roles nature’s first responders are providing to achieve my artistic vision, supporting my sculpture. I consider the needs of other species from the bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and insects to the small mammals, birds, and humans whose life work supports my work. I know that the small systems have to be right for the global systems to run smoothly and I see that too much is at risk to resort to pesticides. I create ways that weeds’ delicately shaped blooms can work in my living land art.

From a practical standpoint, weeds are convenient, cost-effective tools in my human-made nature scape, a catalyst for environmental change, Symbiosis. So, while intellectuals debate the ages, I get out of weeds way, pull over to the right and let the weeds do their job.

In Wikipedia, weed is “of unknown origin.” Ironically, weeds are of unknown origins in most landscapes. So I break down the word weed into three parts.

We – all of us, me, you and I.

ee – In the English language, double e’s are a tool to

denote one connected.

ed – denotes verb, performs an action.

Holocene or Anthropocene? In this age of uncertainty, if humans “weed out” weeding, can all species win the battle? — I wonder…

Additional Weed Readings

WEEDS Control Without Poisons, by Charles Walters.

WHEN WEEDS TALK, by Jay, L. McCaman — includes charts with the functions of each species.

I purchased my copies on Acres USA.

Wood-sorrel exhibits nyctinasty, likely helping the plant conserve energy. It forms a taproot and is upright when young, but as it grows, its long, multibranched stems eventually flop over and trail out along the ground for as much as two feet, extending rootlets from nodes along the stem. This root is beneficial in breaking up the clay. Sorrels contain oxalates, a naturally occurring molecules that bind with calcium. If your soil needs calcium, keep the wood-sorrel.

Youngia japonica a member of the aster family and related to the dandelions. Dandelions Taraxacum officinale shows up when soil is low in calcium and compacted. The local bees, butterflies, birds, and I enjoy the blooms while the dandelion roots break up the clay. Their leaves are loaded with antioxidants and used by herbalists for many health issues.

I believe the above plant to be Cudweed. Cudweed is host for the American painted lady butterfly.

Why we shouldn’t rag on ragweed? The seeds of ragweed are rich in fatty oils. Fats are not only Ebut also is for fattening up birds and small mammals such as Eastern Cottontail, Meadow Vole, grasshoppers which eat the leaves, Dark-eyed Junco, Brown-headed Cowbird, Northern Bobwhite, Purple Finch, Mourning Dove, American Goldfinch, and the Red-bellied Woodpeckers to get them through the lean winter months.

It is an ancient grain for humans and ragweed is a valuable food source for the caterpillars of many butterflies and moths including the striking wavy-lined emerald and the uniquely adapted bird dropping moths. The seeds of ragweed are rich in fatty oils. Birds and small mammals readily consume ragweed seeds to help fatten up for the lean months to come.

I will use this post to document my experiences with weeds.

Documenting the art of creating living soil. SOILED — Tighty-Whities 2021

SOILED — Tighty-Whities 2021

Photograph by N. Baker

How do you document art that lives beneath our feet? Creating art beneath the Earth’s surface I am finding new ways to document the work and it's movement. This photograph is the result. Let me explain. To test soil for fungi that recycle wood and live on dead material soil, scientists buried cotton fabric. In Symbiosis, to document the Saprophytic fungi, I planted new, washed men's medium cotton briefs. This photograph demonstrates the results. In 2022 I will recreate the piece and grow the tighty-whities in a vertical column. This change will document that living soil, the diversity of microbes is built from the top down. In contrast, when my father farmed in the 50s and 60s, the farm bureau that advised him told him to invest in a new plow to dig deeper to access the richest soil.

The purpose of my work is to change how we see landscape. It isn’t just about creating beautiful gardens. Landscape can store carbon and soak up rainwater to cool the planet. It is the cheapest and fastest way to get our planet back on track.

Digging up the briefs I immediately knew I had made a mistake. I left them In the garden’s soil too long. Still, I dug them out with tender care. The petroleum-based elastic band was entwined with a plant root. The root took the elastic leg 6” deeper into the earth than I planted it. I left the elastic and the root as I found them. Laid them on a board and took them immediately to Nash’s photography studio to document the work.

First, I delicately untangled the elastic. The cotton had completely decayed. The elastic was not biodegradable.

Seeing that the briefs were still intact minus the cotton and plus the root I started reassembling the briefs and the added appendage.

In art many times you have to listen to the materials.

the Lipan Apache, bison and Nature Conservancy

In El Paso, where I spent most of my life, the native American tribes had a strong presence in the community. They were responsive and easy to contact. When I started Symbiosis, I reached out to the only tribe I could find Through emails and calls. No one responded. I was hoping to learn more about native plants. The American Indians have a reputation of having a strong connection to nature and bison. Since the native Americans from the Coastal prairie were not able to respond to my requests regarding Symbiosis, I did not try again regarding Endangered Knowledge:The Soul if Humus. It was an intense year working on two huge works, I did not have a moment to think about the relationship between the native Americans and the bison. It was a year of treading water. This article from the Houston Chronicle paints a gorgeous picture of the connection of the Native Americans from the San Antonio area the Lipan Apaches. I would love to meet them, I have reached out. Stay tuned.