This post will serve as a journal for the work.

“My four-year-old daughter saw her first butterfly and was terrified." – Lawndale Art Center patron, 2022.

This remark, shared during one of my Symbiosis artist talks at the Lawndale Art Center, sparked Passionate for Pre–K. Imagining a generation untouched by the gentleness and fragility of wings—this is a sorrow too heavy to bear—and do nothing.

Wildlife plays a vital role in early childhood brain development. At the very least, let each school day begin with a procession past living poetry: vines sculpted in fragrant blossoms of lemon honey, trembling with the promise of caterpillars, alive with the fragile ballet of butterflies. Each child develops in the company of nature’s intelligence.

With small acts of passion, this is within reach.

DESCRIPTION

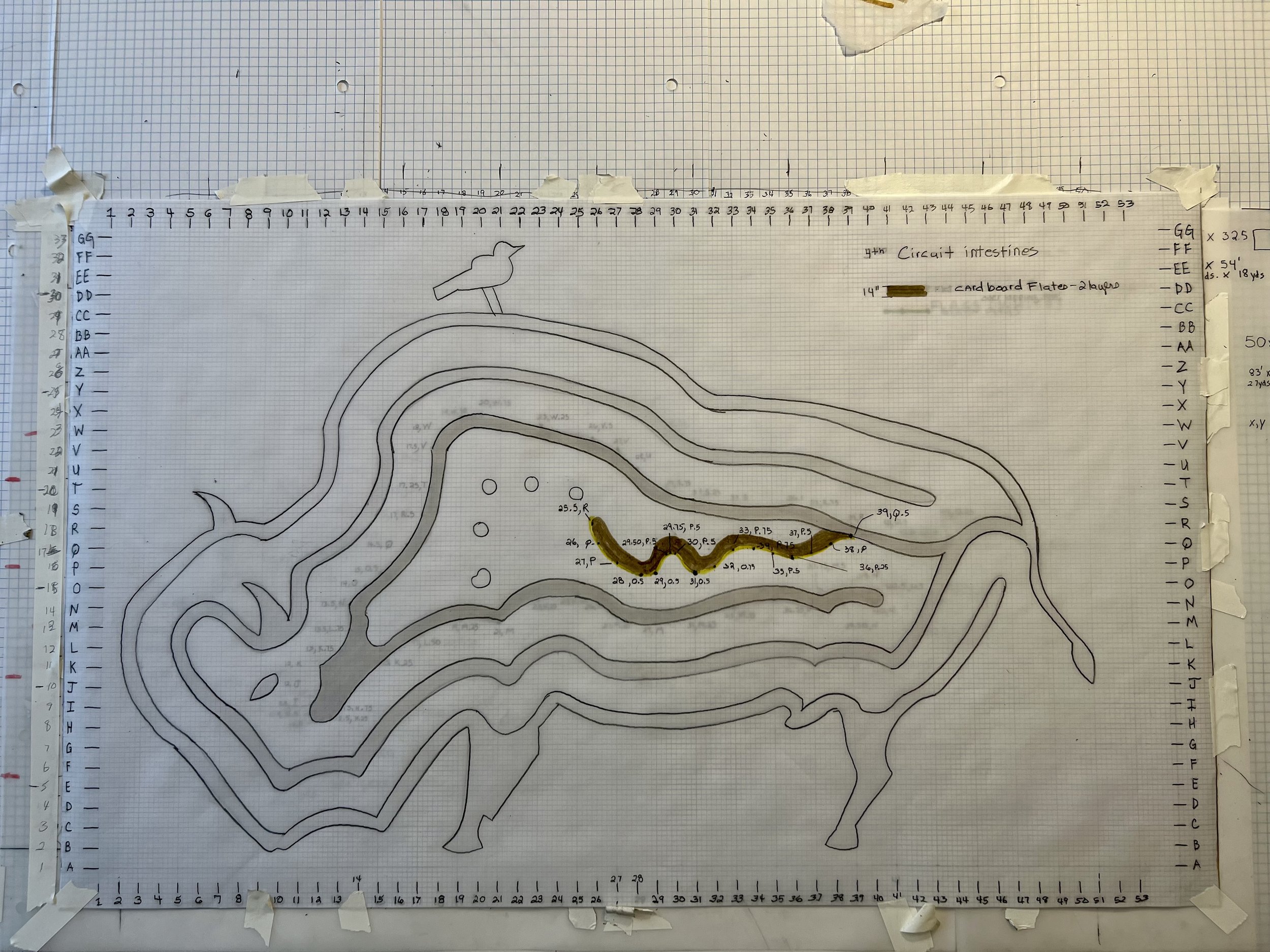

Passionate for Pre–K is a living social sculpture installed in the fall of 2025 on the chain-link fences surrounding the playground at Clemente Martinez Elementary School in Houston, Texas. I sourced 90ish Texas native vines from my three living sculptures: Symbiosis at the Lawndale Art Center, Deeper Than That at a private residence, and Sequel, located next to my art studio in Acres Homes. Passion vines are highlighted in the mix. Sourcing from multiple locations supports the DNA diversity of the ecosystem. Hope Stone and landscape architect Caroline Craddock are coordinating this installation with the school administration.

THE PROCESS

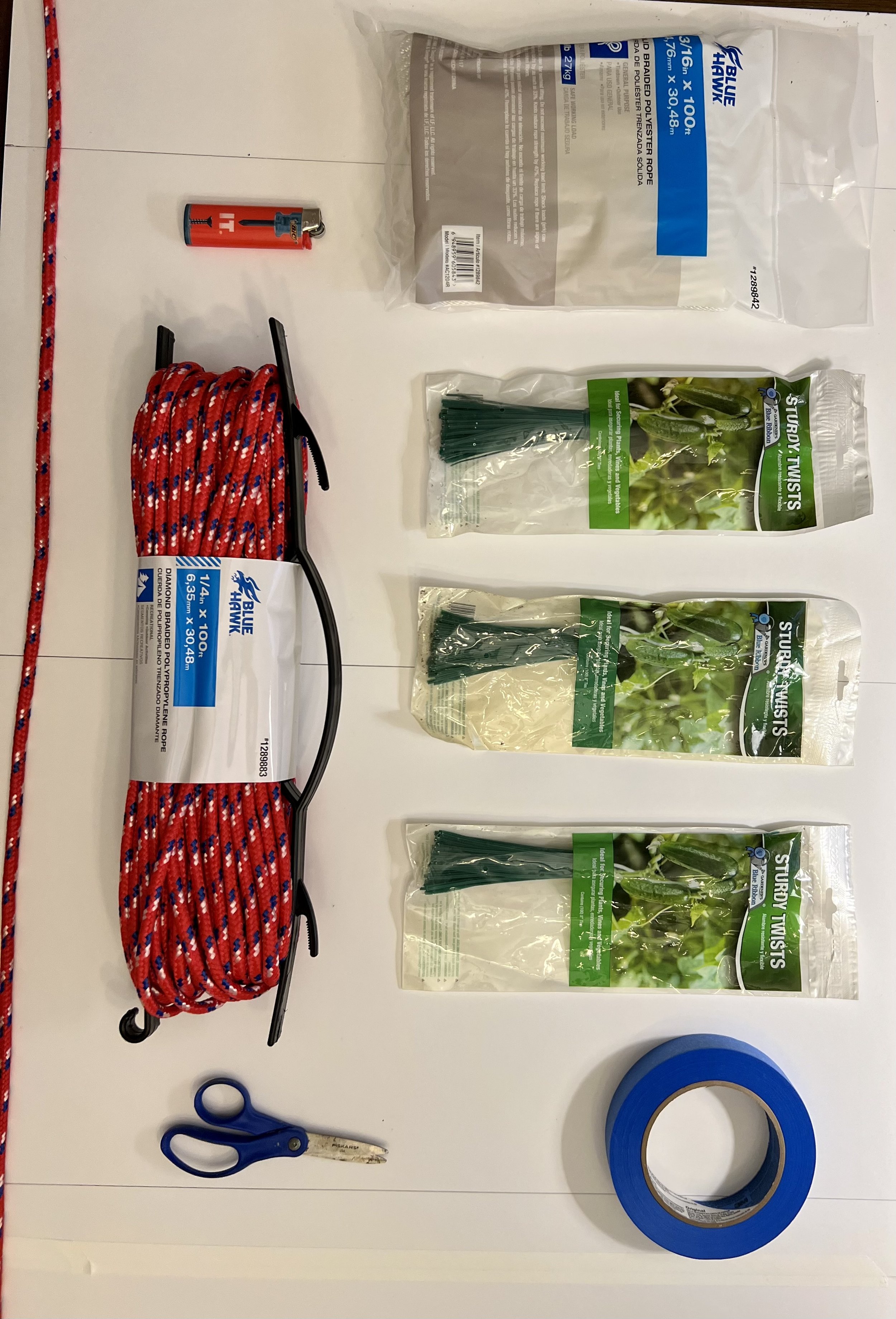

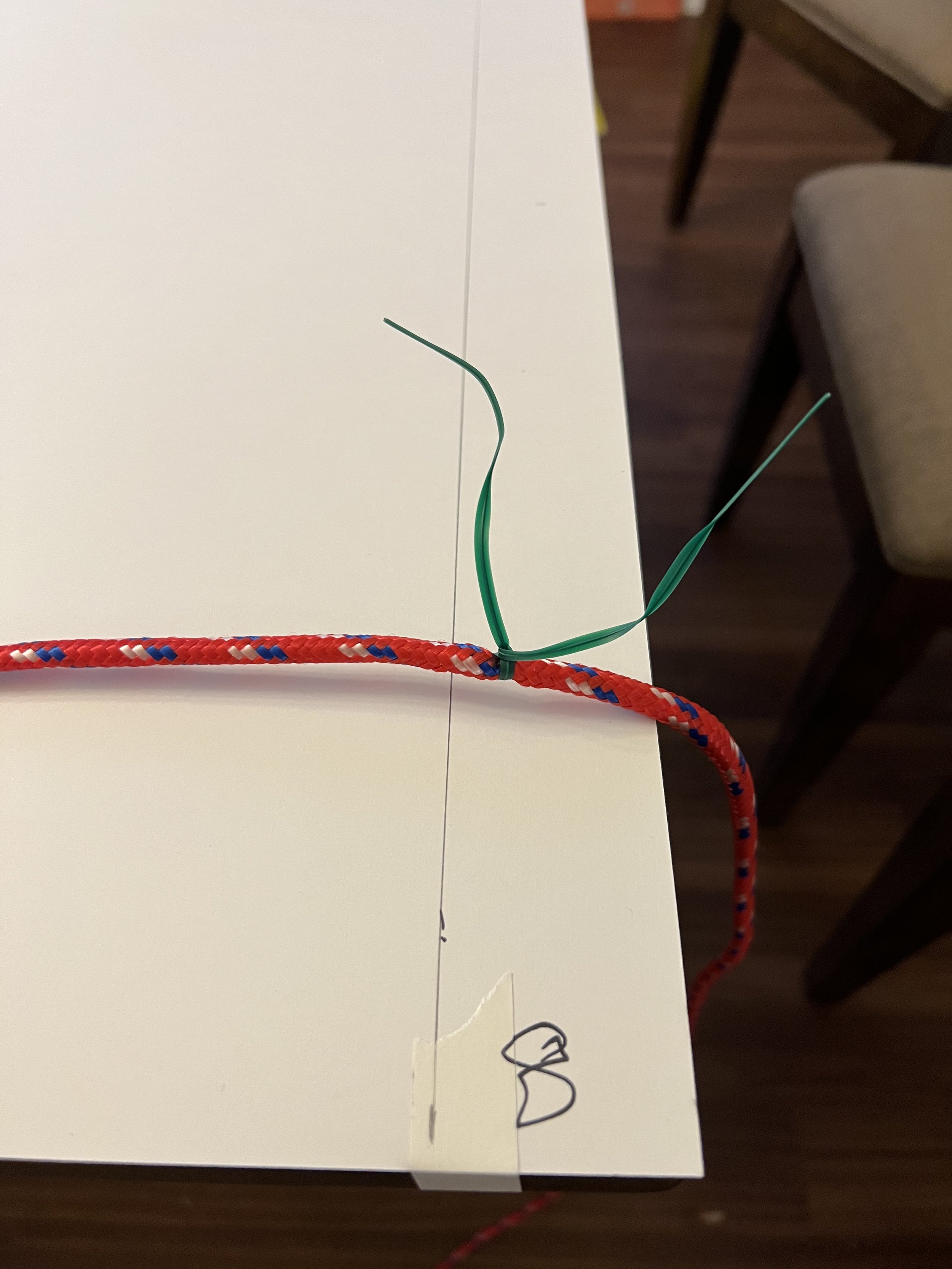

Taking tender 10-inch vine cuttings, using root stimulator and native leaf mold to propagate the plants. I am selecting 90 plants of different species to support a variety of wildlife and accommodate different growing seasons. The school community assisted with the planting in early October.

LONG-TERM GOAL

As ecological knowledge from Symbiosis has taken root in Deeper Than That, which has grown into Sequel, the hope is that Passionate for Pre-K will act as a catalyst. Annually, new tendrils—carefully propagated—will be gifted from Clemente Martinez Elementary School to neighboring schools, allowing the spirit of regeneration to spread from playground to playground, blossoming into a living legacy of wonder and natural intelligence.

PLANT LIST

May pop, Passiflora Incarnata

Stinking Passion vine Passiflora foetida

Various proven Passion vine hybrids.

Trumpet honeysuckle, Lonicera sempervirens

Hairy clustervine, Jacquemontia tamnifolia

Muscadine grape, Vitis rotundifolia

American wisteria, Wisteria frutescens

Crossvine, Bignonia capreolata

Carolina jessamine, Gelsemium sempervirens

COLLABORATION

Passionate for Pre-K is a collaboration with Hope Stone, Caroline Craddock and the Clemente Martinez Elementary School community.

I am extremely thankful for this opportunity, which wouldn't exist without Hope Stone, Caroline Craddock and the incredible volunteers.

NOVEMBER 2025 UPDATE

During phase two of Passionate for Pre-K, a fifth-grade class carefully planted the remaining plants for the installation. The following week, the eager students returned to check on their plantings, only to find a scene of destruction. Unfortunately, a child left unattended in the play area pulled up several plants, leaving only 7 of the original 90 still alive. This act of vandalism is heartbreaking and frustrating, but it highlights how important this project is. The lessons a garden can teach about social responsibility, care, and wonder are fundamental. I will not let one act derail the project. Every child has the right to be inspired by nature. I am propagating new cuttings in preparation for planting again in the spring.

—special thanks to Caroline Craddick for capturing these moments in photos.

One of the plants from the previous planting that was part of the vandalism. Notice the gulf Fritillary butterfly hiding in the shadow.

propagating a passion vine in water.

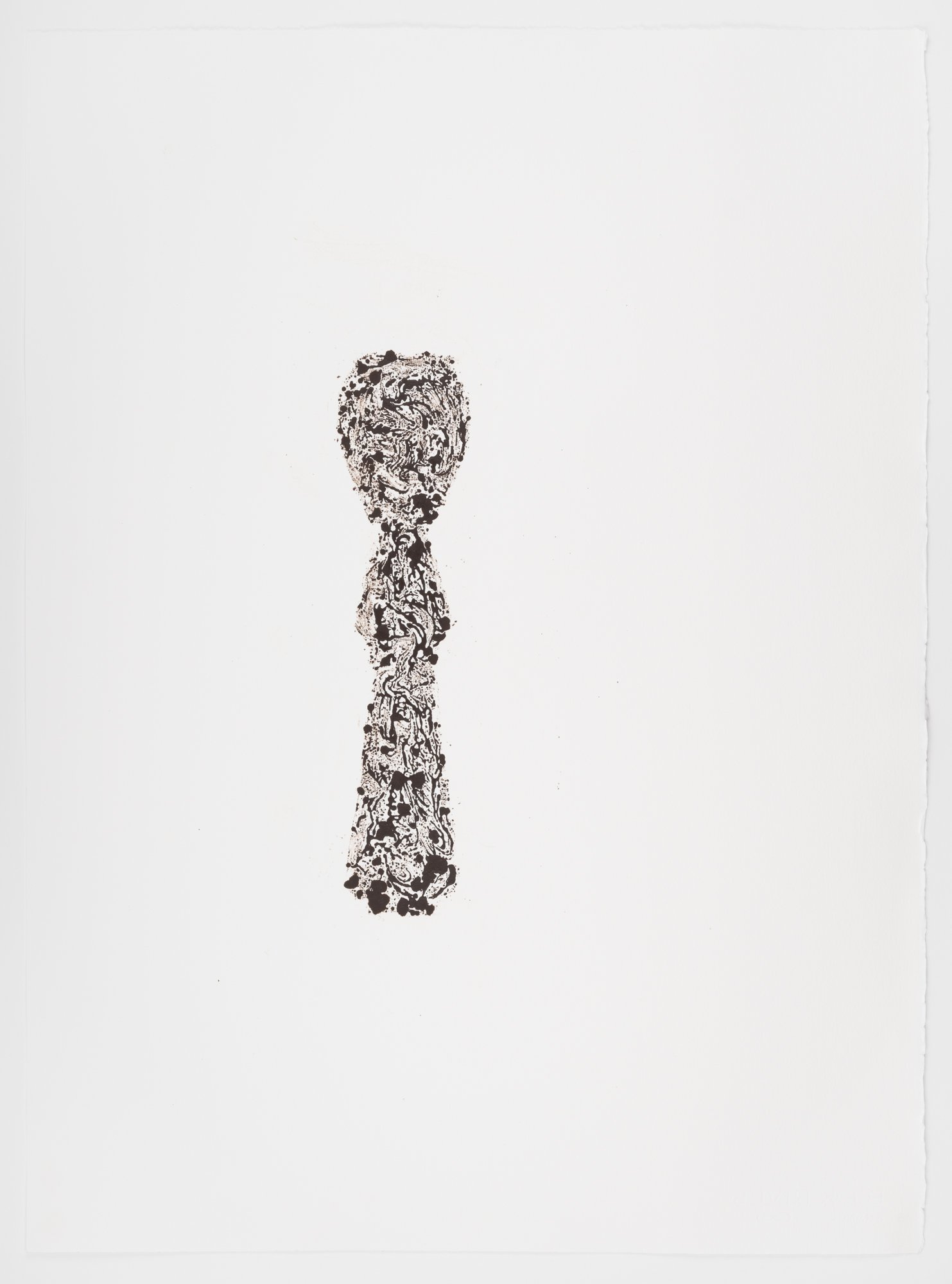

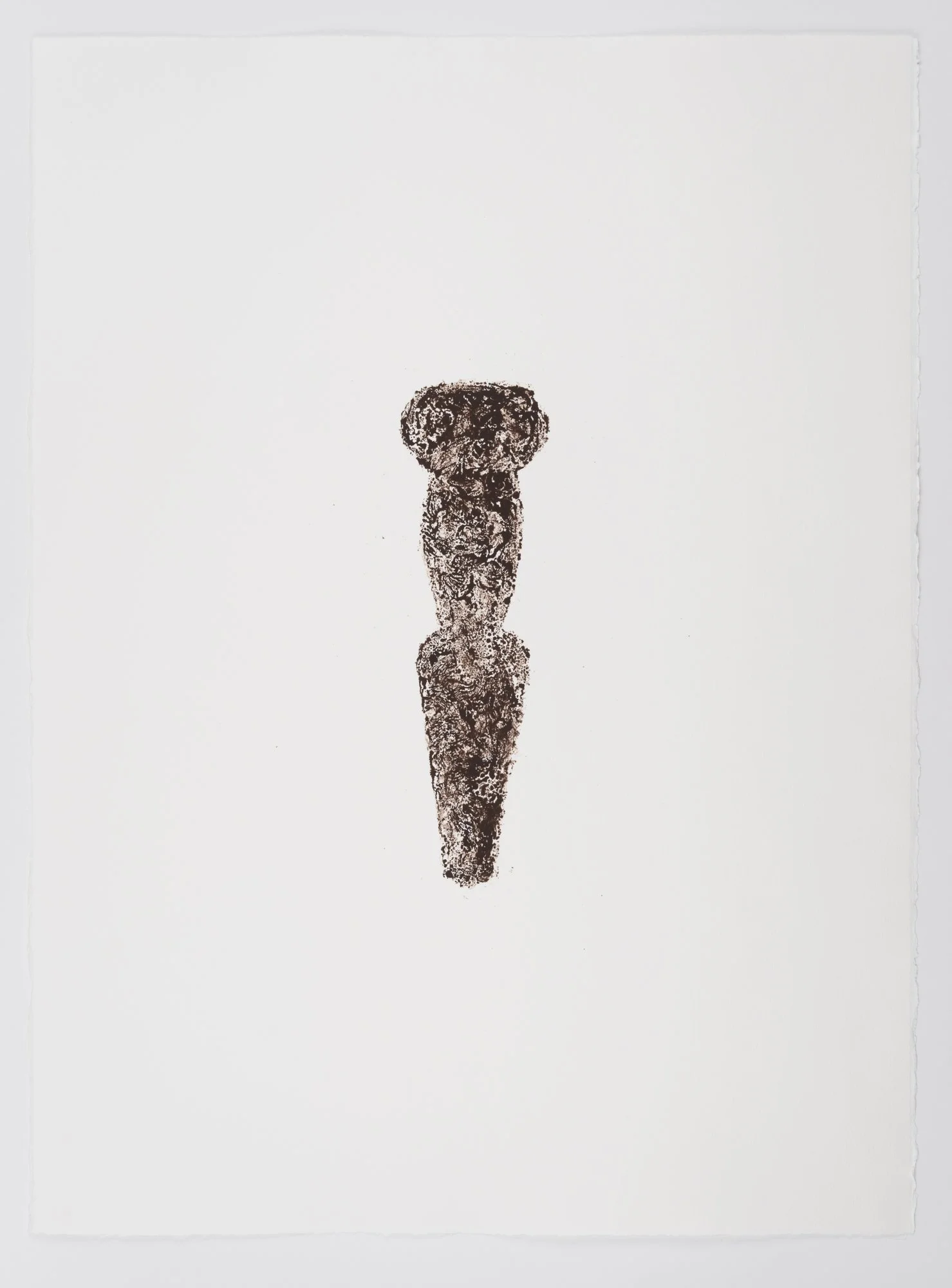

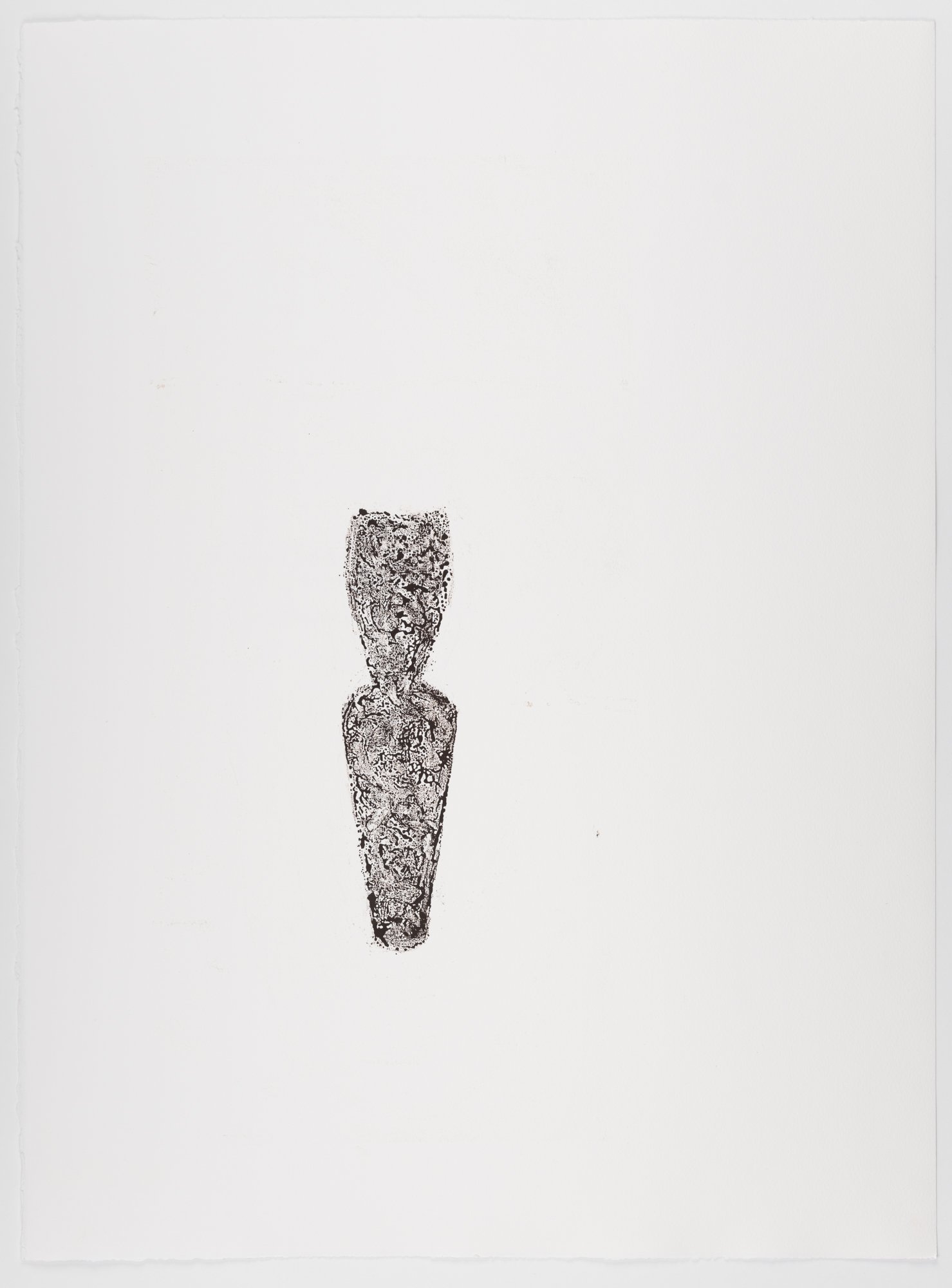

The Stinky Passion flower’s scientific name is Passiflora foetida. It is also known as Fetid Passion Flower, Love-in-a-mist, Wild Maracuja, and running pop.

It has sticky, feathery, leafy bracts that surround the flower and fruit. When an insect tries to eat the fruit, it gets caught in the sticky bracts and dies. The plant then secretes a digestive enzyme and absorbs the nutrients.